microcorruption - reykjavik

Mar 6, 2018 · 8 minute read · Commentsctfexploitassemblymicrocorruptionreykjavik

This post is part of the series of solving microcorruption.com ctf challenges which continues from the previous challenge called Cusco. This challenge is titled Reykjavik.

This challenge has the following description towards the bottom:

This is Software Revision 02. This release contains military-grade encryption so users can be confident that the passwords they enter can not be read from memory. We apologize for making it too easy for the password to be recovered on prior versions. The engineers responsible have been sacked.

Rough. But ok, time to see of its better this time. Also, “military-grade encryption”, hah! :P

reykjavik

The main routine this time is a quite a bit different when compared to the previous challenges:

4438 <main>

4438: 3e40 2045 mov #0x4520, r14

443c: 0f4e mov r14, r15

443e: 3e40 f800 mov #0xf8, r14

4442: 3f40 0024 mov #0x2400, r15

4446: b012 8644 call #0x4486 <enc>

; once enc is done, call something without a label?

444a: b012 0024 call #0x2400

444e: 0f43 clr r15

Only two call’s are made in main, of which the second has no label.

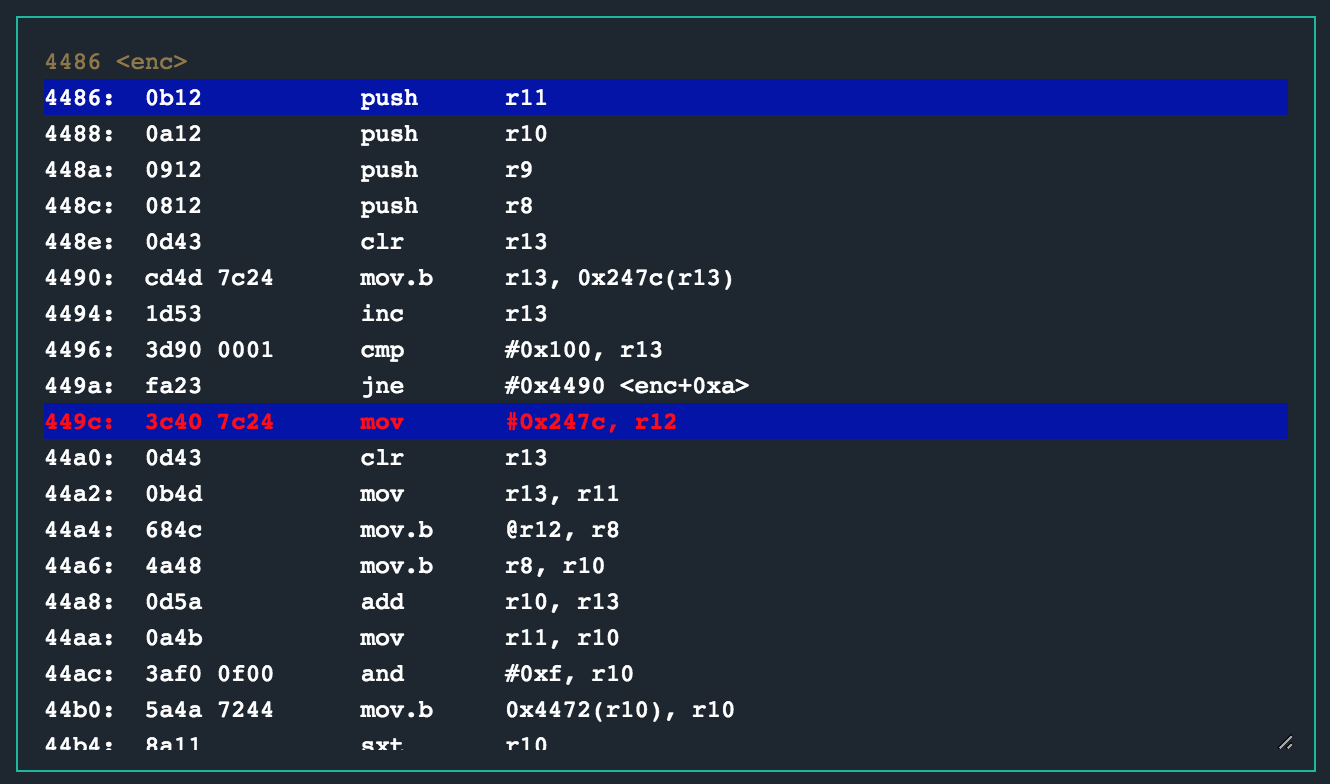

The enc routine has quite a bit of logic though. Taking a closer, annotated look at the enc routine as I was performing a static analysis resulted in the following:

4486 <enc>

4486: 0b12 push r11

4488: 0a12 push r10

448a: 0912 push r9

448c: 0812 push r8

; clearing r13, might mean that the instruction at

; 4490 will move a 0x0 byte into 0x247c, indicating

; the start of a loop

448e: 0d43 clr r13

4490: cd4d 7c24 mov.b r13, 0x247c(r13)

4494: 1d53 inc r13

; this looks like a loop that will continue until

; r13 is incremented up to 0x0100 (256). interestingly

; that is bytes 0x00 to 0xff...

4496: 3d90 0001 cmp #0x100, r13

449a: fa23 jne #0x4490 <enc+0xa>

; not sure what this is preparing for yet, but it looks

; like r11 is being setup for a loop here.

449c: 3c40 7c24 mov #0x247c, r12

44a0: 0d43 clr r13

44a2: 0b4d mov r13, r11

44a4: 684c mov.b @r12, r8

44a6: 4a48 mov.b r8, r10

44a8: 0d5a add r10, r13

44aa: 0a4b mov r11, r10

; some arithmetic. maybe an indication of a decrypt of

; some sorts or a simple byte swap happening here, needs

; debugger

44ac: 3af0 0f00 and #0xf, r10

44b0: 5a4a 7244 mov.b 0x4472(r10), r10

44b4: 8a11 sxt r10

44b6: 0d5a add r10, r13

44b8: 3df0 ff00 and #0xff, r13

44bc: 0a4d mov r13, r10

44be: 3a50 7c24 add #0x247c, r10

44c2: 694a mov.b @r10, r9

44c4: ca48 0000 mov.b r8, 0x0(r10)

44c8: cc49 0000 mov.b r9, 0x0(r12)

44cc: 1b53 inc r11

44ce: 1c53 inc r12

; the loop with r11 for another 256 bytes

44d0: 3b90 0001 cmp #0x100, r11

44d4: e723 jne #0x44a4 <enc+0x1e>

44d6: 0b43 clr r11

44d8: 0c4b mov r11, r12

44da: 183c jmp #0x450c <enc+0x86>

44dc: 1c53 inc r12

44de: 3cf0 ff00 and #0xff, r12

44e2: 0a4c mov r12, r10

44e4: 3a50 7c24 add #0x247c, r10

44e8: 684a mov.b @r10, r8

44ea: 4b58 add.b r8, r11

44ec: 4b4b mov.b r11, r11

44ee: 0d4b mov r11, r13

44f0: 3d50 7c24 add #0x247c, r13

44f4: 694d mov.b @r13, r9

44f6: cd48 0000 mov.b r8, 0x0(r13)

44fa: ca49 0000 mov.b r9, 0x0(r10)

44fe: 695d add.b @r13, r9

4500: 4d49 mov.b r9, r13

; probably the actual decryption taking place here, as

; r15 (which was set in main) is used as an offset.

4502: dfed 7c24 0000 xor.b 0x247c(r13), 0x0(r15)

4508: 1f53 inc r15

; decrement r14 until we get to 0, which will prevent the

; jmp back up from being taken, ending the routine.

; r14 was set to to 0xf8 (248) in main, so that might mean

; that the decrypted bytes is 248 long.

450a: 3e53 add #-0x1, r14

450c: 0e93 tst r14

450e: e623 jnz #0x44dc <enc+0x56>

4510: 3841 pop r8

4512: 3941 pop r9

4514: 3a41 pop r10

4516: 3b41 pop r11

4518: 3041 ret

As you can see, this is a busy routine. There is very clearly some form of byte write, swapping and xor occurring as expected. Some key points to note though is that the memory location 0x2400 that was written to r15 in main is used as a starting offset for an xor instruction occurring within enc. So, that is definitely an interesting location to watch as we debug this routine.

debugging

To gain a better understanding of what is happening in enc, I set a breakpoint at the entry point of this routine with break 4486. Then continuing the CPU and manually stepping through the instructions while watching what happens around memory address 0x2400 revealed the following:

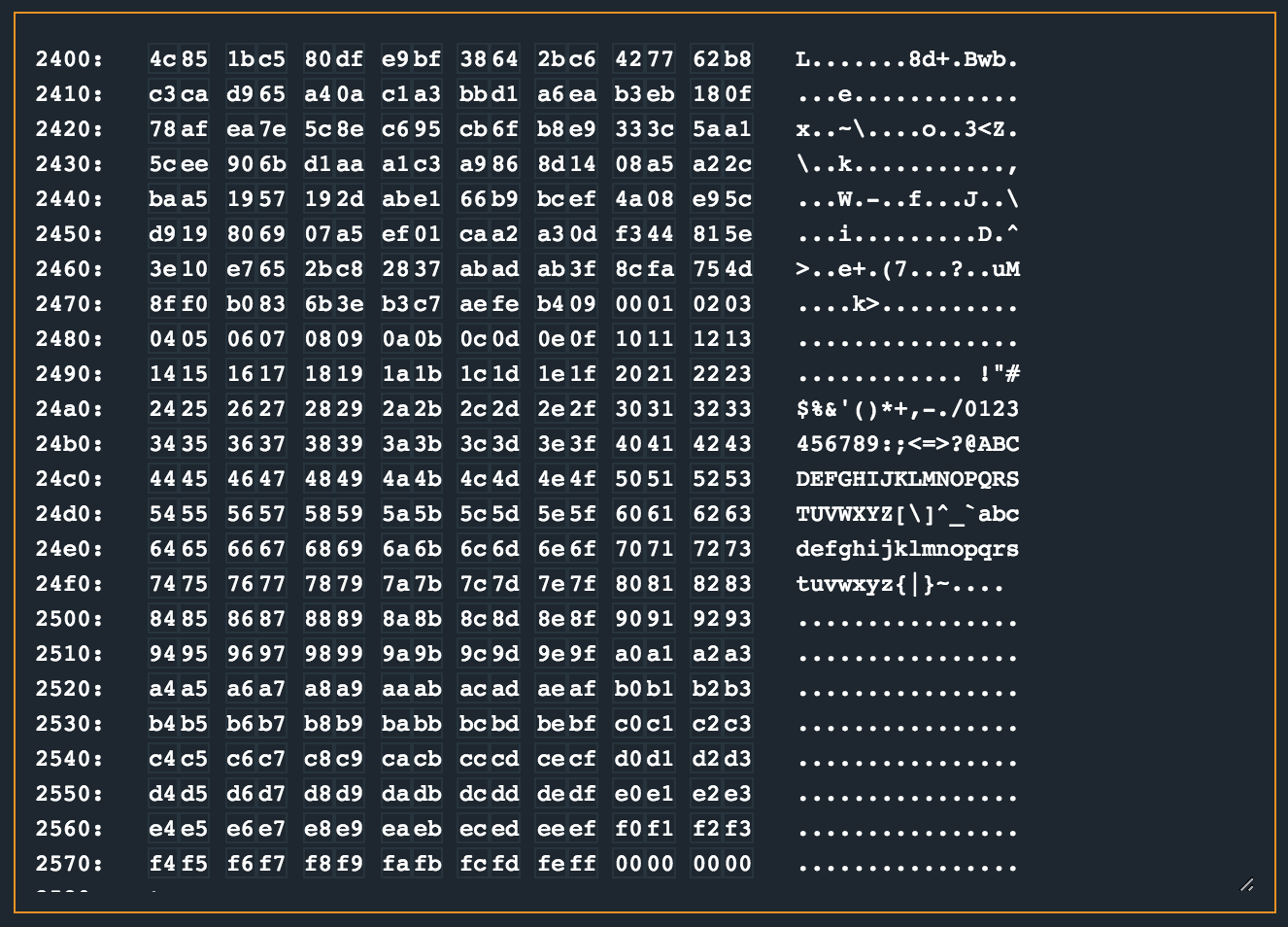

It looks like a payload already lives from 0x2400 and a range of bytes from 0x00 to 0xff is written from 0x247c onwards.

This memory state is achieved right after this loop has completed and the jump at 0x449a is not taken. Alright. Lets move on. The next loop also does a whole bunch of manipulations on the byte range that was just written to memory (and a few other things). There are some weird instructions like the mov.b r11,r11 at 0x44ec that I couldn’t quite understand, but nonetheless.

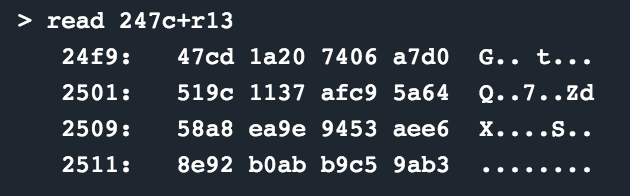

The most important thing to see in this loop is that the bytes at 0x2400 are XOR’d with those at 0x24f9 when the xor.b 0x247c(r13), 0x0(r15) instruction is called the first time. The second time, 0x247c(r13) calculates to 0x24b6, which is the next XOR.

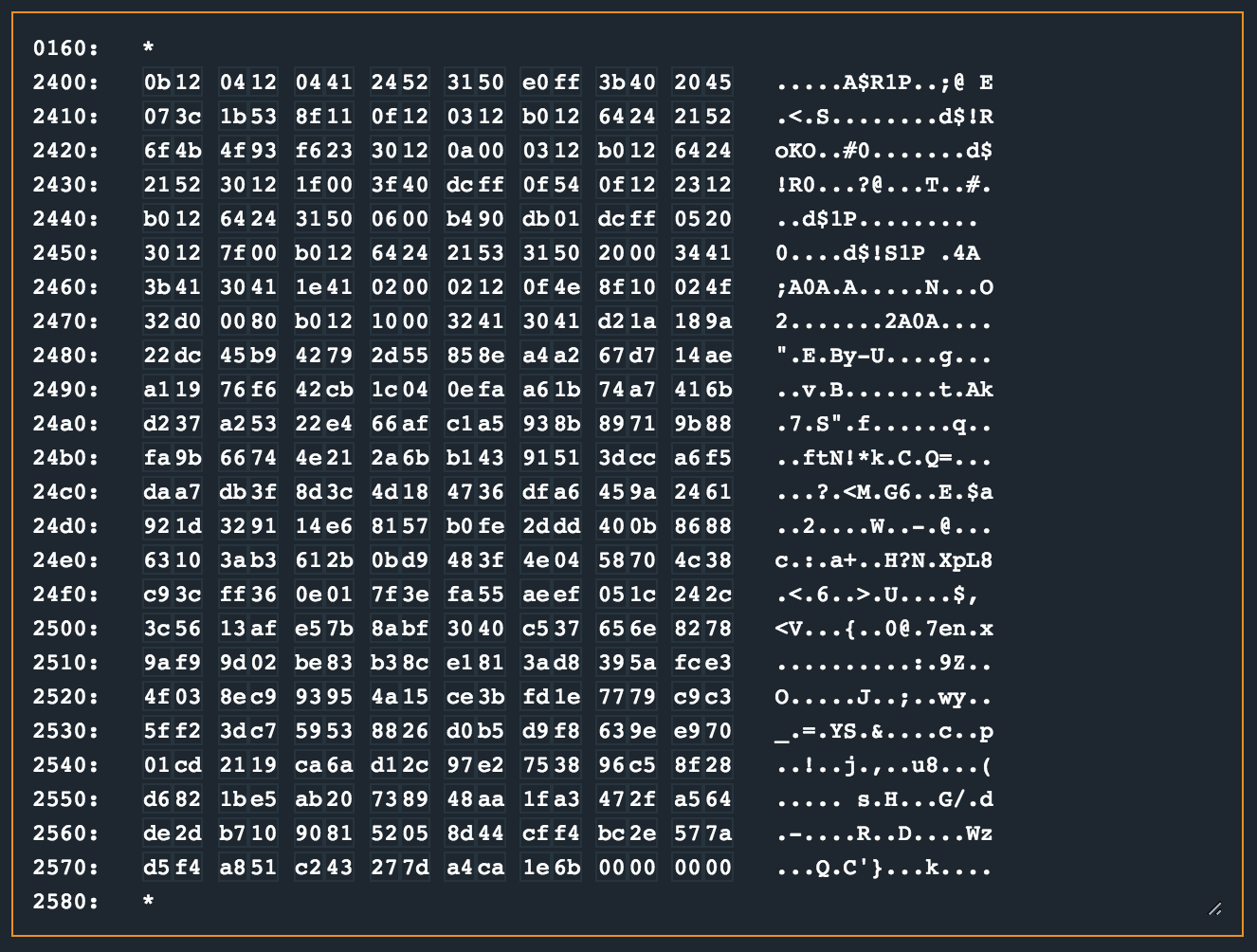

This loop continues until r14 reaches zero, and the registers before the call to enc is restored and the function returns. At this stage, the memory contents at 0x2400 looks as follows (which should now be the decrypted contents):

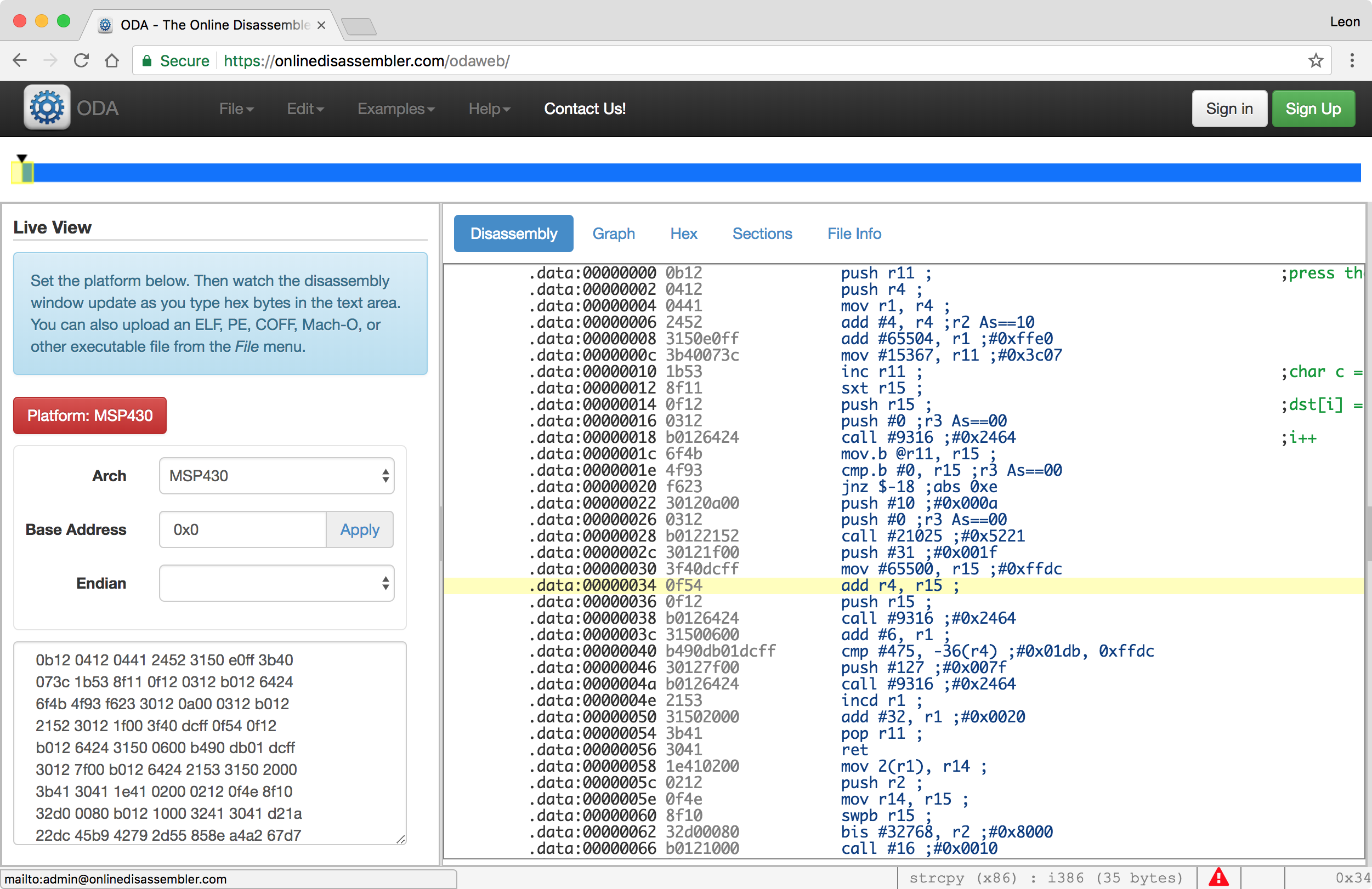

At this stage its pretty clear that the call to jump to 0x2400 in main was because then the encrypted opcodes would be available there and further processing should take place. Now, reading the opcodes like that from a memory dump sucks. So, to make it a little more digestible, I slapped the dump into https://onlinedisassembler.com. The process was pretty simple; select the memory dump from microcorruption, paste it into a file, cleanup the dump with cat dump | cut -d" " -f2-11 and paste that result into the RAW section in the disassembler. Finally, set the architecture to MSP430 and profit!

After pasting that into the disassembler, I quickly realised that the whole payload might not be valid code for this section. After the ret the instructions became pretty crazy, so I just removed those. The final opcodes I used (which was ~256 bytes when counted with cat dump.raw | tr -d ' ' | wc -c) were:

0b12 0412 0441 2452 3150 e0ff 3b40 2045

073c 1b53 8f11 0f12 0312 b012 6424 2152

6f4b 4f93 f623 3012 0a00 0312 b012 6424

2152 3012 1f00 3f40 dcff 0f54 0f12 2312

b012 6424 3150 0600 b490 db01 dcff 0520

3012 7f00 b012 6424 2153 3150 2000 3441

3b41 3041 1e41 0200 0212 0f4e 8f10 024f

32d0 0080 b012 1000 3241 3041

Anyways, I could now step through these instructions in the debugger, and have a disassembled reference I could refer to and see what is happening. The opcodes in the online disassembler would also correspond with those on microcorruption at the top right section which helped confirm that I was on the right track.

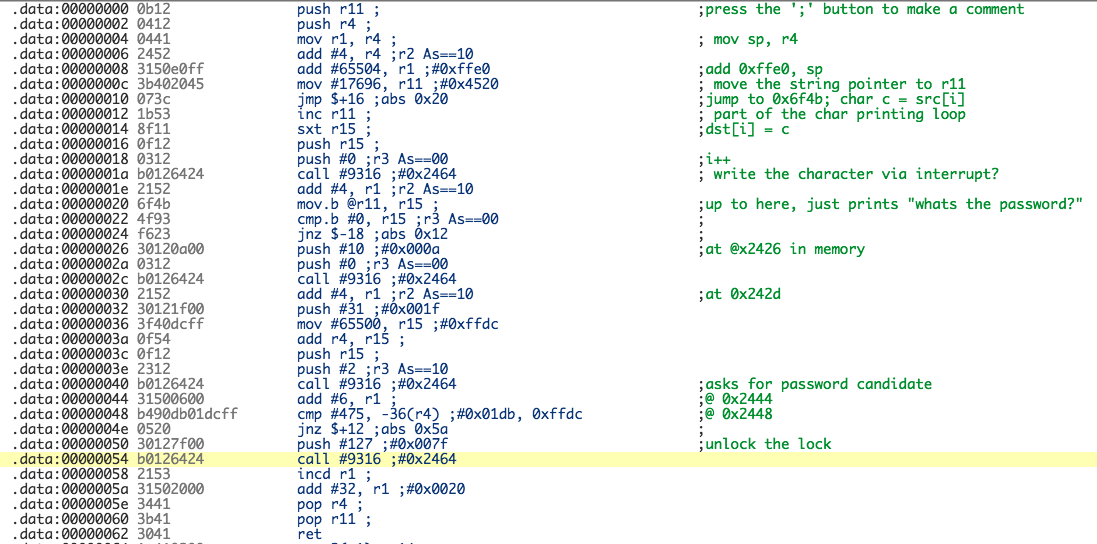

Stepping through each instruction, annotating what I thought was happening helped me understand what was going on. After a few rounds of running the routine, the following instructions were the most interesting as they were the instructions called just before it would jump away from the unlocking logic.

cmp #0x1db, -0x24(r4)

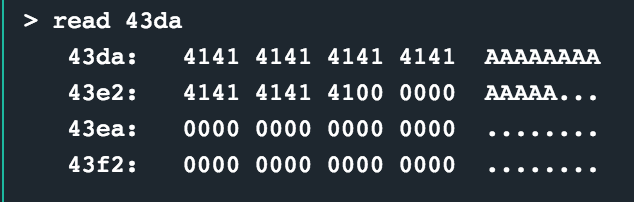

jnz $+0xc

I needed to see what is happening at -0x24(r4) and see if I can control that value. To help me locate the memory location of the data used for the cmp, I had to do a little offset calculation. First, the cmp instruction was at 0x2448, found by simply looking at the program counter (pc) as I debugged the routine. A breakpoint here let me inspect the registers and perform the offset calculations needed to know what data was used in the cmp. Register r4 contained 0x43fe which is 17406, so taking 0x24 (36) from that ends you up with 0x43fe.

>>> 0x43fe

17406

>>> 0x43fe-36

17370

>>> hex(0x43fe-36)

'0x43da'

The data at 0x43da was the start of my password buffer, which is effectively what is being used in the cmp instruction. Making sure my password entered started with 0xdb01 (remember, little endian) would be enough for this compare to result in the status flag being set to not have the next conditional jump taken, resulting in a value of 0x7f being pushed to the stack and a syscall being made to unlock the lock!

My final, annotated version of the dissasembled opcodes looked as follows:

solution

Enter db01 as hex encoded input.

other challenges

For my other write ups in the microcorruption series, checkout this link.